West Bromwich Albion are delighted to welcome you to the official platform celebrating the 125th Anniversary at The Hawthorns.

Supporters are encouraged to visit the platform regularly throughout the season for updates as we celebrate our prestigious anniversary.

Floodlit cricket has become central to the very existence of the game in recent times, such that all the major cricketing venues have pylons towering over them to facilitate day / night Tests, T20 and the Hundred.

The idea for playing cricket in the evening came from Australia, when Kerry Packer’s World Series Cricket pioneered the plan in the early 1980s. Installing floodlights for what then seemed at best a few days of use per summer was an expensive business, so it was some years before the likes of Edgbaston were kitted out.

Nonetheless, having seen floodlit cricket on the TV, there was an appetite to see it in the flesh in this country, and so football grounds were employed instead, including The Hawthorns.

On 29 July 1987, a meeting of India and Pakistan was arranged in aid of the Children’s Society and Imran Khan’s benefit. Imran was skippering the Pakistan side in England, having drawn the fourth Test at Edgbaston on the previous day, while many of the Indians were playing county or club cricket across England.

The matting pitch was laid in the centre circle, lengthways, such that the batsmen were playing straight drives into the Brummie and the Smethwick, or looking to pepper the short boundaries of the Halfords Lane and the Rainbow Stand sides with hooks and cover drives. If ever a game was set up for the batsmen…

Organised at very short notice, it unsurprisingly left a bit to be desired. Nobody had thought to provide a scoreboard – the half-time board in the Woodman Corner really wasn’t up to the task. Worse, neither side provided a scorer, so amid the orgy of runs, nobody was entirely sure what the score was. And after rain delayed the start, the sightscreen blew over. And so many balls were smacked out of the ground over the short boundaries that after one six sailed, quite literally, somewhere over the Rainbow, there had to be an appeal for the ball to be returned as they were running out of them.

But let’s not lose sight of the fact that this was still a game between Pakistan and India, one that carried all the weight which that implies – it remains sufficiently important for the eventually decided upon scorecard of the game to still sit on the Pakistan Board of Cricket’s website.

Pakistan batted first and in their allotted 35 overs, they smashed 278 for 6, Mansoor Akhtar top scoring with 73, Manzoor Elahi hit six sixes in an over, while Kirti Azad took two wickets for India in conceding 82 runs from five overs. India responded in fine fashion, Raman Lamba scoring 90, Dilip Vengsarkar weighing in with 72 as India won by four wickets with five balls to spare.

As some of you are doubtless shouting at your screen now, The Hawthorns had hosted floodlit cricket prior to the meeting of India and Pakistan. We know, we know, but that’s another story for another day…

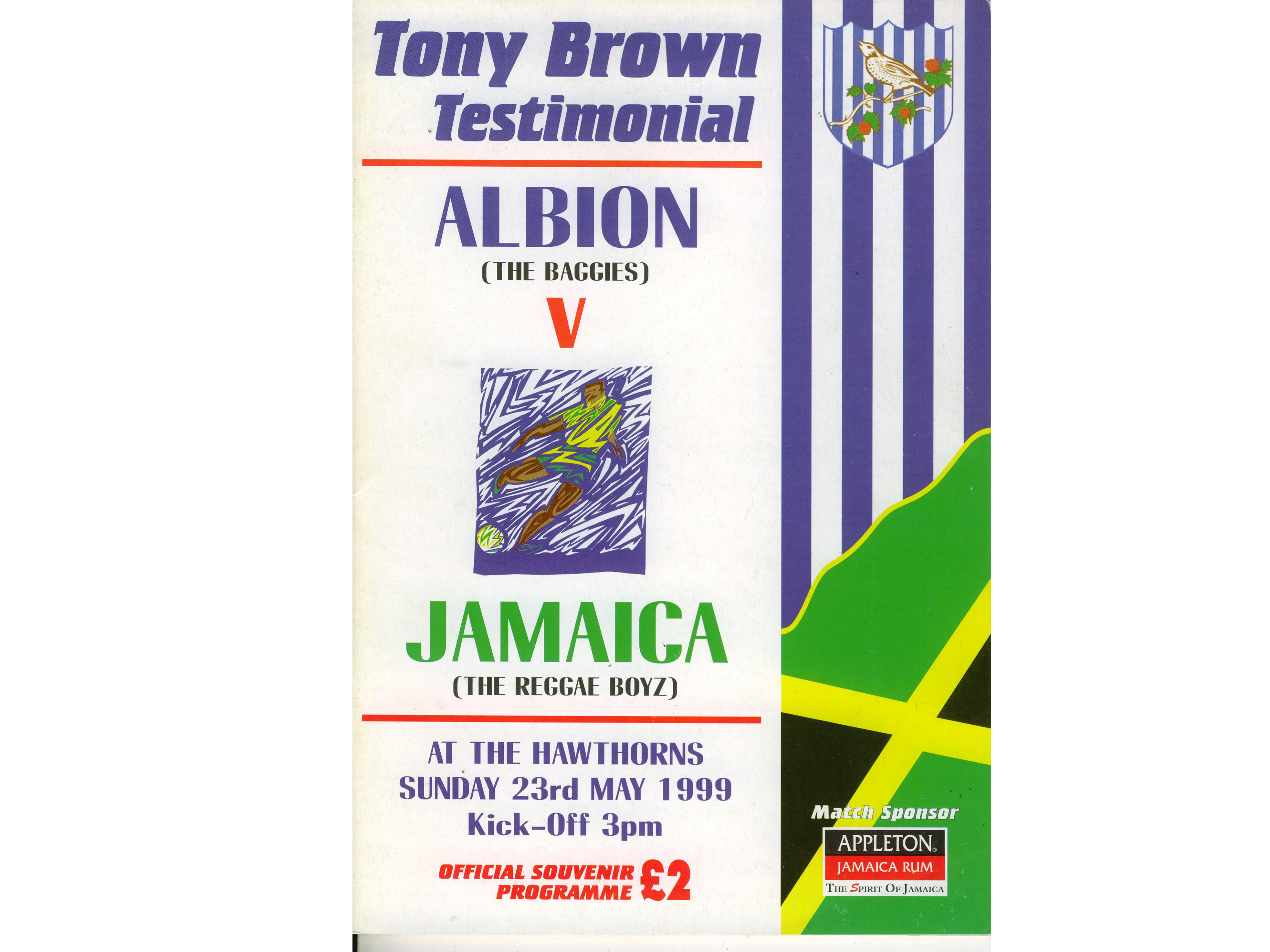

The relationship between Tony Brown and West Bromwich Albion will crop up more than once in this series, no surprise given that he played more games and scored more goals here in senior football than anyone else.

Like any longstanding relationship, there were the odd few moments of stress the worst coming in 1981. Although Tony’s playing career essentially ended in the 1979/80 season, Albion boss Ron Atkinson kept him involved with the first team and had promised a second testimonial to follow the 1974 game that he had enjoyed. But when Atkinson left for Manchester United in the summer of 1981, Bomber was told his services were no longer required. He left for Torquay United and the testimonial was shelved.

The idea was floated on and off through the 1990s before the Club put right the wrongs of the previous decade and granted Tony a second game at the end of the 1998/99 season, staged at The Hawthorns on May 23.

“It was great that the club decided to give me the game, but then it was about finding a team to play,” Tony recalls. “Playing Jamaica was a very unusual idea, but it went down a bomb in the end. At the time, I thought it was a big gamble. I wondered if we’d get a decent crowd, and I had to pay a lot of money to bring them over, so I was sweating!

“But it proved a great success, and it all happened in the last week or so when it just went crazy. The ticket office was besieged, they were queuing all day. People from the Jamaican community had told me that was how it would be. They said everybody would want to come, from all over the country, but they wouldn’t get their tickets until the last minute - they were spot on.

“The Reggae Boyz had fantastic support then, the year after the World Cup, and their fans came from everywhere, not just locally, to see the game. I remember a few days before, the West Indian team had played a cricket match at Bristol and a few of us went down to give leaflets out to the crowd, advertising the game!

“It was a great crowd, a wonderful atmosphere on the day, unbelievable. A few of the old boys came back for a game before the main match, then Bryan Robson and John Barnes played for Albion against Jamaica. It was great, very touching, a really emotional day.

“The thing was I’d never been in the Brummie Road End and I said right from the start that if I got a testimonial, I was going to watch it from in there. I tell you what, it was an experience on its own. Absolutely brilliant! Well worth the wait, just for the atmosphere. It made the day for me. What a great memory to keep.”

Some 20,358 packed The Hawthorns for the game, including world boxing champion Lennox Lewis, who made a half-time appearance. Jamaica won the game 1-0, Marcus Gayle getting the winner early in the second half, but it really didn’t matter. The supporters had had the chance to pay homage to Tony Brown one last time.

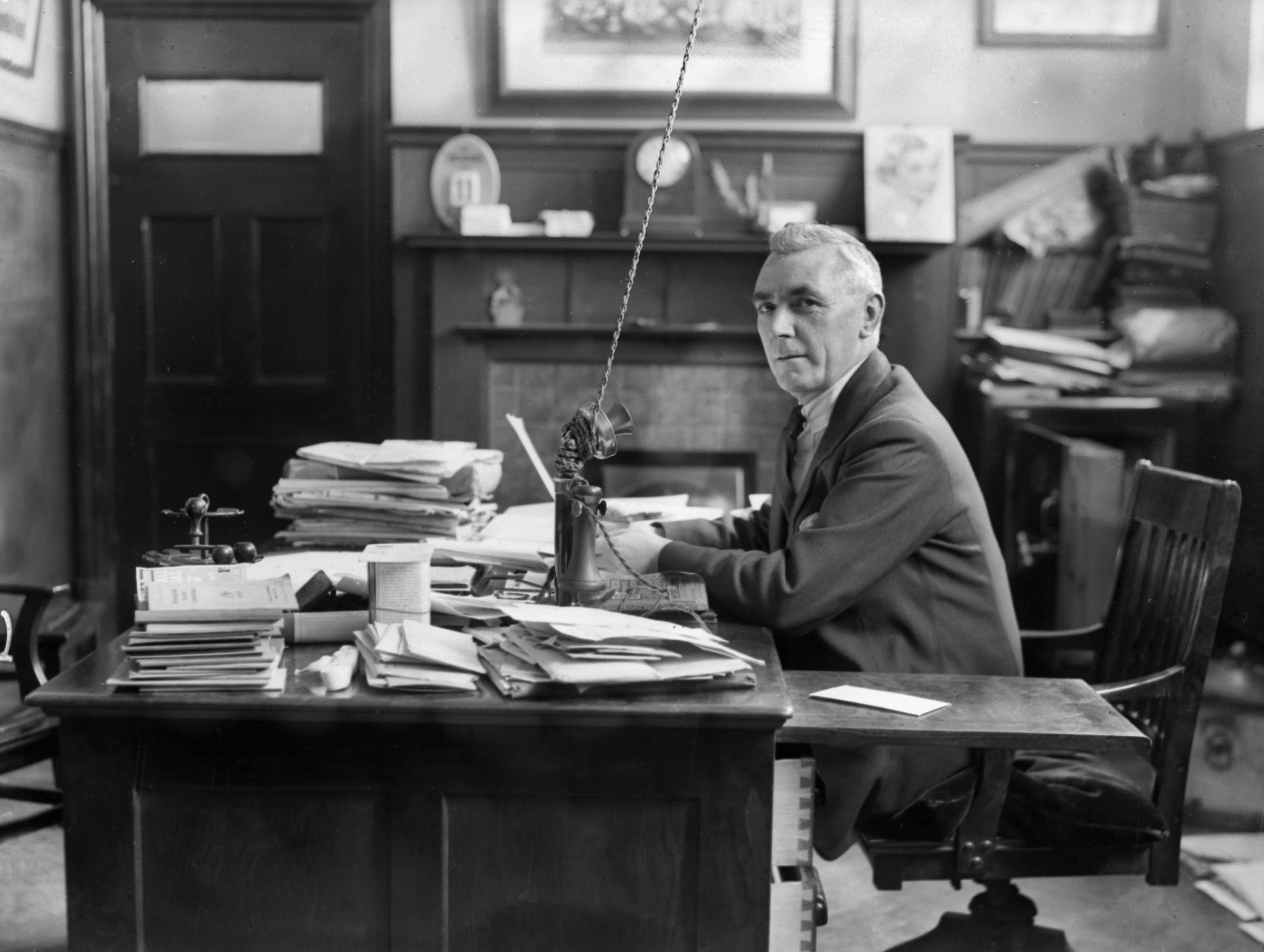

We’ve talked about Fred Everiss in this series already – keep up, there’ll be a test later – but not only was he the man who invented the future at The Hawthorns, he future-proofed the club’s administrative functions too.

His assistant, Ephraim Smith, joined the Albion in 1906 and went on to succeed Fred as club secretary upon his retirement at the end of the 1947/48 season. By then, Eph was a member of the Everiss clan, having married Fred’s sister in 1911.

In post when Albion won the FA Cup in 1954, Eph presided over the arrangements for one of the most important developments that ushered in a new age, the installation of floodlights at The Hawthorns. He also had to organise he increasingly frequent foreign tour, including one to the Soviet Union in 1957.

Eph held the post of club secretary until his own retirement in 1960, whereupon the role was taken up by Alan Everiss, Fred’s son. Alan joined the Albion in 1933 and all but matched his dad’s longevity here, enjoying 20 years as secretary through to 1980 when he finally hung up the club fountain pen.

Where Fred had helped guide the club through the rapid expanse of the game in the early 20th century as organised football became a staple of the English way of life, Alan picked up the reins as the game was heading in a new direction with the advent of regular televised football just around the corner. European competition was something new that would be coming to The Hawthorns too, while there were more and more regulatory demands to deal with in terms of stadium safety, particularly as hooliganism became an increasing issue in the 1960s.

Tony Brown’s playing career coincided with Alan’s time as secretary, and Bomber had the highest regard for him.

“I knew Alan very well. He did a fantastic job here, he was absolutely immaculate in everything that he did. Alan had the club running like a well-oiled machine, like clockwork. Everything was just so completely under control, run smoothly, it was all spot on. Any problems that might crop up, Alan would be on top of it straight away and sorting it out. He was meticulous in everything that he did, left nothing to chance, he was on top of every little detail.

“A lot of the time, you dealt with him on contracts rather than anybody else – not that you got much say in those days! That attention to detail meant everything was done right, never any issues, no mistakes, no blunders, nothing like that. He was a very clever man, very experienced.

“During my time, the club started to jet off around the world a bit more, whether it was in the European competitions or for friendlies in China, the Middle East, America, wherever. I’m sure in those days, it wasn’t the easiest thing to get the paperwork done for trips like that, because they were so unusual then, but with Alan, you never had to worry, it was all in hand, so easy from our perspective as players.

“In truth, as far as the administration went, Alan virtually ran the club from top to bottom because there was only a handful of staff here in those days. He’d take the load off the manager and allow them to concentrate on the football. He had an assistant – initially it was Freddie Horne, then Ray Fairfax came in later on – and both of them learnt a lot from Alan, but he was always in charge, on top of things.

“To add to all that, he was a lovely fella as well, very easy to talk to, very well liked throughout the club. He had a dry sense of humour too. He was a real unsung hero of the football club.”

We talk of Billy Bassett, of Jesse Pennington, of Tommy Glidden, the great Ray Barlow and Tony Brown, and so we should. But when you want to speak of the men who mattered most in Albion’s long story, Fred Everiss’ name must ring down the ages along with all of those. For he was an Albion man, heart and soul.

It’s only right and proper that administrators keep a low profile and that the power and the glory should go to the players who produce the on field deeds that propel a club forward, create history, build a legacy. Even so, behind the scenes, the wheels need greasing, the machine needs oiling if the game is to go on, if the players are to be allowed to perform, if the club is to be able to survive and thrive. That is the job of the administrator.

During football’s infancy a century and more ago, the club secretary would also double up as team manager, although the team itself would ordinarily be selected by a committee of directors. Albion went through a number of these secretary / managers before, on the departure of Frank Heaven, we came upon a figure who was to create a dynasty, Fred Everiss taking on the role in 1902.

If some come into football today having been seduced by the apparent glitz and glamour of it all, Fred was under no illusions when he came on board as “a very perky Throstle aged 13, my wages being four shillings a week. That did not worry me for what appealed to me was that I should be able to see the matches for nothing.

“We had a ground called Stoney Lane (mind you, I have heard it called other things as well) and our offices were in High Street, up three long flights of steps which saved us from many troublesome callers who did not fancy the climb. And we did not fancy them. In those days most of the letters we received began with the word “Unless”.

“In 1900 we moved to The Hawthorns against much opposition although I think if we had stayed at Stoney Lane we would have gone out of existence. The staff – that is the boss [Frank Heaven] and I – moved there too, an office having been provided for us on the ground, and our ups and downs there for the first ten years outrivalled any scenic railway in the world.

“I was called before the directors in 1902, and although I had not asked for the job, I was appointed to succeed Mr. Heaven who had just resigned from the secretaryship of the club, and I was then aged 19”.

Everiss was fortunate to take over an Albion ascendant for the club had just won Division Two the previous season, spending only one year in the Football League’s basement before marching imperiously back to the top table. But tumultuous times were in the offing as the club lacked the quality of player that it had employed in the golden period of the late 1880s and early 1890s. Within a couple of seasons, relegation beckoned again, and though the enclosed Hawthorns was an infinitely better theatre for football, Albion’s struggles meant they weren’t drawing in the crowds they’d hoped for.

The club was on a downward spiral and in 1905, though we finished 10th in Division Two, we were a mere three points away from having to apply for re-election to the Football League. Financially we were in freefall after a series of mishaps that season, including one on Bonfire Night 1904 when Noah’s Ark, the old stand painstakingly transplanted from Stoney Lane, burnt to the ground. More than £4,000 of damage was done, while to rebuild the stand would have cost £1,600, money the club did not have, not least because the insurance payout of £951 went straight into the hands of the creditors.

By the end of the season, we were in tatters, the bank serving a writ against the board in an effort to get back the money it was owed. The board resigned, Harry Keys returned as chairman, former Albion great Billy Bassett joined the new board and Albion limped on, not least thanks to the efforts of Everiss who went cap in hand to other clubs – Aston Villa and Newcastle each donated £50 – and the Birmingham Evening Despatch who set up a shilling fund to raise £401.

Yet as Everiss recalled, it looked no more than a stay of execution. By the end of 1909/10, though results had improved on and off, we were still in Division Two. “In 1910 I had to call a directors’ meeting to decide whether we should carry on, because our financial position was such that we had been advised by experts to close down. Only one attended and that was Mr. Bassett who was chairman.

“A decision had to be made entailing all the summer expenses and finally we decided to continue, the cash being provided by Mr. Bassett, Mr. Harry Keys and Mr. Dan Nurse, neither of whom were directors just then, and myself”. Without those four men, you’d currently be doing something else with your Saturday afternoon.

The club realised they were drinking in the Last Chance Saloon now and Bassett placed his faith in his young manager, still only 27. The two took it upon themselves to completely rebuild the playing staff, understanding that Albion’s only means of survival was, as ever, via results – if we won games, people would come. It was to be expected that Bassett could spot a player, but his eye was no more finely tuned than Everiss’. They scoured the locality, asked for reports from local contacts and had the courage to act upon their convictions.

“When the [1910/11] season opened, I hadn’t a bean in the world, it had all gone to the Albion and I suppose I was a sort of super optimist. But we had a marvellous season and finished up by winning the championship [Division Two] and the club found itself with plenty of money, our debts were paid and everything was set fair again.

“A year later we reached the Cup Final and with the cheque we received as our share, purchased the freehold of The Hawthorns and so everything was, for the first time in our history, the club’s own property”.

With Everiss presiding over day to day matters alongside Bassett, Albion established themselves comfortably in the top division and, when the Great War meant the cessation of footballing hostilities at the end of the 1914/15 season, they were looking like the coming force. Everiss continued to work diligently such that when the game returned in 1919/20, Albion were ready.

The club stormed to the First Division title for the only time, racking up a record 60 points and scoring over 100 goals. It was the fulfilment of every dream that Everiss might have had for his club which, quite rightly, immediately recognised his extraordinary contribution by making him a Life Member of the club, an honour later bestowed on his son Alan too.

The workload was becoming extreme, for Everiss had team responsibilities to contend with along with scouting and signing duties, on top of which were added the administrative requirements of his post, which were yet more onerous.

Everiss was so utterly dedicated to his job and to the club that the workaholic would often put in an 18 hour day, ensuring that everything went smoothly. But in this game, it’s never quite that simple because competition must always mean there are winners and losers. In 1926/27, we were on the wrong side of the equation and relegation placed the icy fingers on the shoulder and gathered us in.

Were we discouraged? We were not. Everiss and Bassett simply saw that there was work to do and began to reinvigorate the side once more, as they had in 1910. To more seasoned campaigners such as Tommy Magee, Joe Carter and Tommy Glidden were gradually added more youthful prodigies such as Harold Pearson in goal, following on from his Championship winning father Hubert, the “Iron and Steel” half-back pairing of Jimmy Edwards and William Richardson. Winger Stan Wood came in from Winsford United, left-back Bert Trentham from Hereford United, and as the 1930s dawned, Albion were the local antidote to the Great Depression.

Another young local, Teddy Sandford, emerged to play inside-right, accompanying the exceptional goalscoring talents of WG Richardson, brought in from Hartlepool. Everiss had been told of his burgeoning skills by Jesse Pennington who had heard about him while on holiday. Everiss got the first train north with Dan Nurse to make sure he was signed, WG recalling, “All three of us trooped off to my house where mother was getting my meal out of the oven. We talked and I agreed to join Albion, signing the paperwork in the front parlour by the aspidistra”.

The biggest aspidistra in the land waved goodbye to the young striker who would be central to the biggest triumph in our history for WG was the spearhead of the 1930/31 team that collected the unique double of winning the FA Cup and promotion to the First Division, giving Everiss the distinction of being the club’s manager in two of the three greatest campaigns in our history (1953/54 as you’re asking), and all within an 11 year spell.

But not even Fred could hold back change and it was clear football was moving towards a situation where the secretary and manager’s jobs could no longer be combined. With the death of Billy Bassett in 1937, it meant even more responsibility was placed on his shoulders. Equally, as he entered his fifties, the immense workload was taking a toll on him. Yet he continued to appear tireless and when war broke out again, he combined the job of secretary with a role as part-time groundsman, no small feat as games continued to be played to keep the home fires burning. He was an ARP warden into the bargain.

It was a different world and a different game when football returned in full order for the 1946/47 season. At the end of 1947/48, it was decided that Albion needed a full time manager. At the age of 66, Everiss took the opportunity to relinquish his secretarial duties too, handing over to his loyal assistant, Eph Smith.

Fred Everiss joined the Albion board thereupon, and remained a director until his death in 1951, a tragically short retirement for one who had given the club and the game so much.

ALBION 2 QUEENS PARK RANGERS 2

22 JULY 2020

The strangest season came down to the simplest equation.

On July 22, 2020, attacking the final round of games in the 2019/20 Championship, the Albion had to beat QPR at The Hawthorns in order to secure automatic promotion. Anything less than that, and a win for Brentford at home to Barnsley would see them sneak into second place instead, while defeat might even let Fulham come through.

On home turf, Albion were surely in the box seat, but in this strangest of seasons, now entering its 355th day, nothing was that simple. Playing behind closed doors because of the Covid pandemic, there was no home atmosphere à la Crystal Palace in 2002 to help drag the side over the line. And with nerves jangling after defeat at Huddersfield Town in the penultimate game meant that Albion had taken just one point from nine, nobody was taking anything for granted.

When Ryan Manning gave Rangers a 34th minute lead, there wasn’t quite panic but there was a pretty uneasy feeling in the collective stomach. But what a difference a dozen minutes can make. By the time the side was back in the dressing room at half-time, Grady Diangana had levelled things up for Albion, while a Barnsley goal in the 41st minute meant that the lead to Brentford was now two points. Fulham were even losing at Wigan.

Calum Robinson made it 2-1 just four minutes into the second half, and the Throstles looked home and hosed. But nothing at the Albion is ever that easy and Eberechi Eze levelled it up just on the hour to place things back on a knife edge, all the more so when Brentford found an equaliser of their own on 73.

If things stayed like that, Albion were up. A single goal for a west London side, be it QPR or Brentford, and it would mean the play-offs.

Thankfully, Albion saw the game out, and Brentford were even good enough to concede a late goal to lose to Barnsley and kick the celebrations into gear those few moments earlier.

The Throstles were back in the Premier League.

Given football’s global domination in the 21st century, it’s sobering to recall that just over a century ago, the organised game was still in its relative infancy when it was thrown into chaos by the onset of the first global conflict, the Great War.

When it began in 1914, league football tried to stumble on, looking to maintain business as usual insofar as it could, tangled up in a web of pre-existing player contracts and other financial obligations, along with absolutely no conception of how long the war would last.

When it became clear that it wasn’t going to be over by Christmas 1914 after all, when crowds plummeted as young supporters set off for the fight and as players too began to enlist in the forces, when the sheer scale of the losses and the horrific nature of the suffering caused became everyday currency, the idea of football going on its own sweet way quickly became distasteful.

The 1914/15 season really couldn’t end soon enough and once the final ball was kicked, the game was mothballed and put into deep storage, only to be dug out again once normality had returned to the world. That normality was a long, long time in coming and the names Verdun, the Somme, Passchendaele and others would have to be etched, deep and savage, into the public consciousness before we could think again of Newcastle, Everton and Albion.

Eventually, as the summer of 1918 turned towards the autumn, there was light at the end of the tunnel and the possibility of peace beckoned from the horizon. On the home front, that exercised some minds most vigorously and wheels were set in motion to restore the national game to the forefront of the national conversation.

A fully fledged return to Football League arrangements was impossible. The war was not yet over, many players – and supporters – were still serving on far flung fields, casualties were still being suffered. Nonetheless, starved of almost any income for some three years, largely moribund football clubs were desperate to start filling the coffers once more. In consequence, regional leagues were discussed and, ultimately, begun, the Football League creating a Lancashire Section and a Midland Section to prevent unnecessary travel.

Albion made it clear from the outset that we would have no truck with such arrangements, the minutes of the August 9th 1918 board meeting noting that at the recent annual meeting of the Football League, we had “expressed the unwillingness of the Directors to allow the Club to take part in any competitive list of league games during the coming season whilst the War is on”.

This was no easy decision for like every other club at the time, we were haemorrhaging funds, but the reasoning behind it was brought savagely home at the next meeting in October when, “The Secretary reported…that he had sent a letter of sympathy to Jesse Pennington on the death of his younger brother in action in France”. While that was going on, we simply could not countenance playing a mere game.

Ultimately, the following month, the Armistice was signed and, gradually, the process of returning life to normal began in earnest for the 1919/20 season. All this was for the future of course. What mattered more immediately was getting some kind of football back onto The Hawthorns to give some entertainment to the locals and to assess the strength of our playing squad ahead of the resumption of the Football League proper that August.

We’d missed the boat in terms of the Football League and so we conferred with officials at Derby County, Aston Villa and Wolverhampton Wanderers, all of whom had also declined to play, in order to set up a small scale competition in the spring of 1919. The games were to be played for charity, the profits to be pooled and divided equally between the clubs “for distribution to charities etc as they may think fit”. And so, the first steps towards the 1919 Midland Victory League were taken.

If the destruction of the Great War had not been enough, Spanish flu was devastating already weakened populations and causing another wave of mass fatalities. It was recorded in the March minutes that both Claude Jephcott and Jesse Pennington had suffered very bad attacks of the virus and were highly unlikely to feature in any of the fixtures that ran from March 29th to April 26th, six games in all.

Indeed, there were concerns that the 35-year-old Pennington would ever recover sufficiently to play the game again. Thankfully, he was restored to rude enough health to skipper the Albion to the First Division title the following season, but neither he nor Jephcott were able to figure in the opening Midland Victory League fixtures, the first of which took place at The Hawthorns against the Wolves on March 29th 1919.

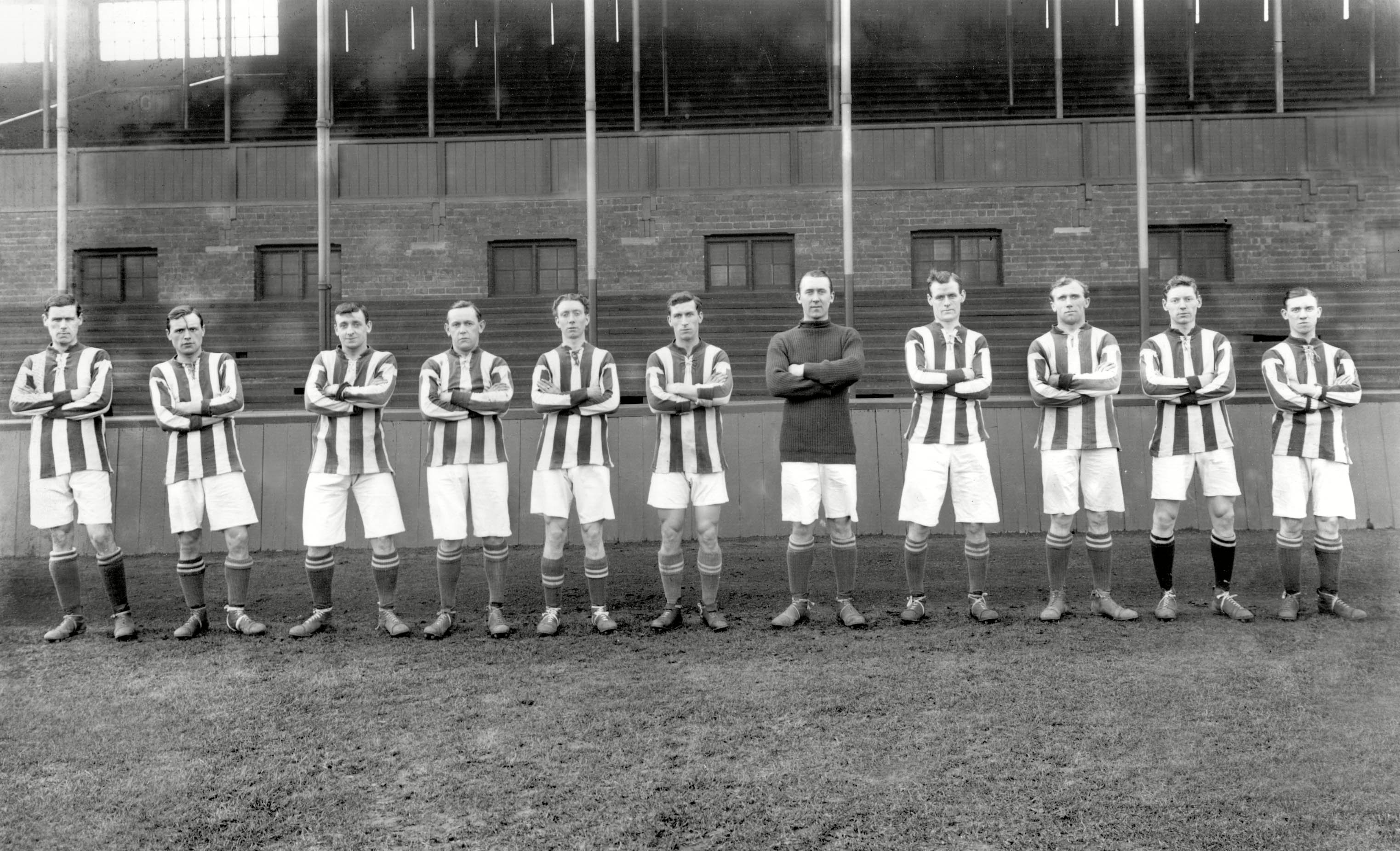

Considering the carnage that had shattered the world over those years of the Great War, Albion’s side had a remarkable familiar ring to it. Hubert Pearson, Joe Smith, Frank Waterhouse, Sammy Richardson, Jack Crisp, Howard Gregory and Ben Shearman were all there from the pre-war side and, over the course of the six games, would be joined by the returning Fred Reed, Bobby McNeal, Alf Bentley, Harry Wright, Sid Bowser, Louis Bookman and Fred Morris.

We needed them back for we started the competition on a low, losing at home to Wolves by the only goal of the game in front of 4,348 spectators. A bright start from Albion failed to yield a goal though Gregory hit the bar, and after the break, Wolves won the game with a goal from Green, though some reports suggest it was Bourne who registered the goal.

Defeat, even to the Wolves, didn’t really matter in the circumstances, for the important thing was that football had returned to The Hawthorns some three years, 11 months and five days since it had been abandoned for the duration. And we could afford to be magnanimous because when the sixth and final game came around, away to Aston Villa, Albion were still in the running to win the competition.

Played in a howling gale on April 26th 1919, the Throstles gave an indication of the whirlwind that the rest of English football should expect in the coming season, opening in imperious form to simply blow the Villa away, Edwards and Morris all but ending the game as a contest inside 22 minutes as Albion raced to a 2-0 lead. Magee duly applied the cherry to the cake with another headed goal from a Wright cross and there we were, on top of the table, the same seven points as Derby and Wolves, but with a goal average of 2.00 compared with their 1.83 and 1.50 respectively.

Perhaps there was going to be a brave new world after all…

There have been plenty of devastating goalscorers who have donned the stripes during these 125 years at The Hawthorns, but certainly as far as the 21st century goes, there has been no better finisher for the Albion than Kevin Phillips.

Signed by Bryan Robson at the tail-end of his reign as manager in August 2006, the fact that Phillips had moved from Villa Park had no impact on the reverence in which he was held by the Throstletariat.

Off the mark with a penalty against Leicester City on his debut Hawthorns appearance, SuperKev wasn’t here for long, but across two seasons, he was the focal point of what became Tony Mowbray’s team of supreme entertainers. Albion topped the century of goals in both 2006/07 and 2007/08 and across that spell, Phillips bagged 46 of them, 26 of them at The Hawthorns.

What more excuse than The Hawthorns’ 125th anniversary do we need to enjoy them all again?

2006/07

Leicester City – 9 September 2006

Leeds United – 30 September 2006

Coventry City – 16 December 2006

Leeds United (FA Cup) – 6 January 2007

Luton Town (2) – 12 January 2007

Southampton – 10 February 2007

Crystal Palace – 14 March 2007

Barnsley (3) – 6 May 07

Wolverhampton Wanderers (play-offs) – 16 May 2007

2007/08

Preston North End - 18 August 2007

Ipswich Town (2) - 15 September 2007

QPR (2) - 30 September 2007

Norwich City – 27 October 2007

Sheffield Wednesday - 6 November 2007

Charlton Athletic – 15 December 2007

Bristol City (2) – 26 December 07

Scunthorpe United (2) - 29 December 07

Crystal Palace – 12 March 2008

Colchester United – 29 March 2008

ENGLAND 1 ITALY 2

21 APRIL 1998

With the European Championships currently in full swing and dominating the national conversation, there is little doubt that women’s football is still enjoying remarkable, rapid growth.

It was not always so.

Back in the 1990s, it was still a game scrambling to get some attention, and so international games were particularly important. Taking the England Women’s team to major stadia around the country, long before they could dream of filling Wembley Stadium as they do with such ease now, was an important stepping stone on the way to today. The Hawthorns played its part, hosting a game between England and Italy on 21 April 1998.

The squad trained at the Birmingham FA’s grounds at Great Barr, the friendly acting as part of the build up to some key fixtures in England’s ultimately unsuccessful attempt to qualify for the 1999 World Cup, team manager Dick Bate in his last months in the job as he prepared to pass the baton on to Hope Powell, who became England Women’s first ever full-time coach that summer.

Albion played their part in trying to drum up support for the game, pegging ticket prices at just £3 for adults, with under-16s able to get in for free, not bad given that league games that season cost from £12 in the Brummie and the Smethwick. It was made clear that the women’s game still had a long way to go when a crowd of just 2,520 turned out for their game, a sharp contrast to the 13,917 that had attended England B against Chile B at The Hawthorns two months earlier, when the men’s side included future Albion men Ricci Scimeca and Nigel Quashie.

Ironically, the games had the same scoreline, England losing 2-1 on both occasions. The women had made a good start against the Italians, taking an early lead when Sue Smith’s corner into the box found Faye White, and she headed into the net.

Italy fought back but England defended well, skipper Gillian Coulthard marshalling the side, and limiting the Italians to few real opportunities. The combative nature of the friendly was underlined just before the break when the Italians lost two players to injury. Roberta Stefanelli limped off following a tackle with Coulthard, then Anna Duo was stretchered off after coming off worst in a challenge with Danielle Murphy, who was booked. Shades of Luigi Riva and the Anglo-Italian Cup of 1971, for those with long memories.

In spite of that, Italy rallied further after the break and they were level in the 70th minute, Patrizia Saerti running onto a through ball to fire past Pauline Cope. England then brought on Rachel Brown in goal, one of five substitutes on the night, but she was also beaten soon afterwards when Piera Maglio fired home a free-kick from 20 yards.

Not the result that England wanted, but nonetheless, it was a big night for some women who would go on to be big names among a trailblazing generation that paved the way for the successes of today.

It proved a successful night for The Hawthorns too, the Football Association full of praise for the way the game had been staged. This plaque was due commemoration of the occasion.

The Birmingham Road, for all its charms, has never been the most architecturally elegant stretch of real estate in the Black Country, but on Friday July 11, 2003, it became a site transformed by the unveiling of the Jeff Astle Memorial Gates at the entrance to The Hawthorns’ East Stand.

Following the tragic death of the King in January 2002, there was plenty of debate about how his life should be properly celebrated, with much discussion between supporters’ groups, the club and, most important, Jeff’s wife, Laraine, and the rest of the Astle family.

At that point in time, physical memorials to former Albion heroes did not extend beyond the naming of suites and executive boxes within the stadium, but Jeff Astle’s passing clearly demanded something more.

Given Astle’s relationship with the support, particularly as the King of the Brummie, that was the location where any tribute simply had to be. Installing a set of memorial gates was the conclusion, constructed along the Birmingham Road itself, next to the stand, running across the East Stand car park, marking the entrance way to the stadium and the main offices of the club.

The project, funded by Smethwick Regeneration Partnership and Smethwick Town Team, alongside generous donations from the football club, Shareholders 4 Albion, Grorty Dick, the WBA Supporters Club and the Boing website, has become a real focal point at The Hawthorns, a place where many supporters meet up before and after games.

Beyond that, the Gates have become a rallying point in good times and sad. When Cyrille Regis, Astle’s great successor in the number 9 shirt, passed away in 2018, the Gates were festooned with scarves, shirts, flowers and all manner of tributes to another fallen hero, taken before his time.

The Gates themselves were designed to honour Astle in real detail, the arch featuring not just his dates, 1942-2002, but the number nine within a crown on each gate – after all, he was the King. The illustration panels feature Astle in the triumphant pose he struck having thumped in the goal that beat Everton to win the FA Cup in 1968, with a bit of poetic licence included to put him in the home kit instead. The panels featuring the club crest were changed after that was updated in 2006.

Fittingly, it was Laraine and Jeff’s grandchildren, Matthew and Taylar who unveiled the gates back in 2003, leaving Jeff looking out over the Birmingham Road, his kingdom, in perpetuity.

Astle is the King. Don’t ever forget it.

ALBION 0 BIRMINGHAM CITY 0

20 JUNE 2020

Some 109 days after hosting Newcastle United in the FA Cup, football returned to The Hawthorns after the Covid hiatus.

Well, football, yes, but not as we knew it.

With all the various Covid protocols still very much in place across the country, with much of it still locked down in all but name, the authorities concluded that bringing football back from its own shutdown was not only vital for the health of the game, but for the morale of the nation.

The only problem with that was that in a world of social distancing, Covid testing and all of that, there was simply no way that the games could be played in front of crowds. The only option was to play behind closed doors, the players performing in front of empty stands (no real change for some clubs not too far from here…).

And so, on June 20 2020, we stepped into a brave new footballing world. At least, the players and the officials did. The rest of us were still stuck in the house, watching the games as they were streamed live to our computers and TV sets.

Albion against Birmingham City was the first game at The Hawthorns, a 0-0 draw somehow appropriate in those bizarre new surroundings, a game also notable for being the first time Albion used five substitutes in a competitive fixture.

Little did we know how long it was all going to last.

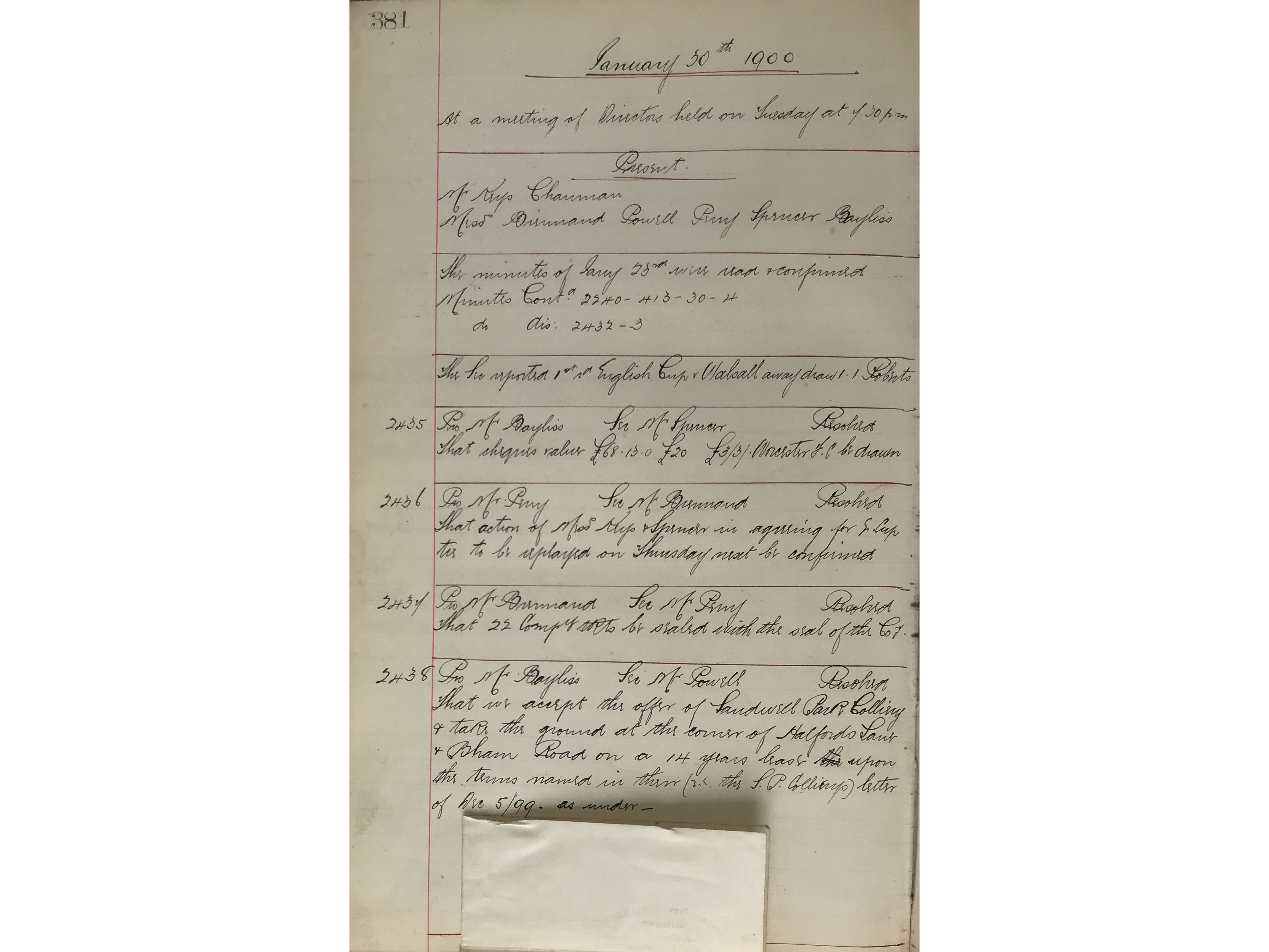

30 JANUARY 1900

January 30th 1900. Queen Victoria was in the 63rd, and final, year of her reign. Lord Salisbury was Prime Minister. The second Boer War was raging. We were still 28 days away from the creation of the Labour Party and 24 hours from the copyrighting of the ‘His Master’s Voice’ illustration of Nipper the dog. But, as we shall see, these are mere trifles compared with the real history of the day. If you’re sitting comfortably, we’ll begin…

At that time, West Bromwich Albion were, undeniably, among the early giants of English football. The Throstles had won two FA Cups, reached three other finals and kicked off the Football League’s history, as well as winning plenty of local competitions, but there is more to running a business than just footballing glory. The difficult sums need to add up as well.

Things were coming to a head as the 19thcentury was heading towards its close along with the end of the Victorian age. A new world was on its way and, as far as football was concerned, it would increasingly revolve around pounds, shillings and pence. On that front, Albion’s rickety old Stoney Lane home made no real sense.

In April 1899, with the club struggling to make ends meet, The Free Press painted a pretty bleak picture both for us and the wider game. “The fact is that with the high prices now ruling for players, and the transfer system, the Albion are placed at an enormous disadvantage in their comparatively poor financial position in securing really good men. The clubs with the longest purse have the best chance of securing the cleverest players. These demands for high wages are gradually killing the game in many towns”. And they say history can teach us nothing.

The problem was simple. You might be able to cram supporters into Stoney Lane for one off cup games, but beyond that, it was lacking in the facilities needed to make it a welcoming venue. Additionally, the ground was only held on a short-term lease and, after some initial enthusiasm for the site, which included the building of the Noah’s Ark grandstand, the club directors soon refused to put any more money into improvements given this was not a permanent home.

With other clubs growing quickly by investing the money now coming in from the better attendances into stadium infrastructure, it meant Albion had perhaps the worst ground in the Football League, certainly in its top division, while the team was also in decline. Albion had survived the drop to Division Two in 1896 only by virtue of coming through the end of season “Test Matches” against Liverpool and Manchester City, an early version of the play-offs.

Stoney Lane was holding the club back and, while in the spring of 1899 Albion entered into a further 12 month lease on the ground, it was clear they needed to move on. Yet nothing is ever quite that simple in football, particularly as we are all so wedded to our traditions and our history. While the directors had already proposed a move from Stoney Lane well before things came to a head in 1899, as the Birmingham Gazette reported, it was an idea that for some seemed to be too far ahead of its time.

“The suddenness of the proposal was too great for a few individuals and a sentimental attachment to the old Stoney Lane ground caused opposition to be raised. Moreover, a number of gentlemen with interests in the vicinity came forward with a proposal to spend £2,500 on the old ground with the object of so improving it as to attract a greater number of people. The opposition was carried to such an extent by interested parties that eventually the owners withdrew the offer of the ground and the whole thing fell through.”

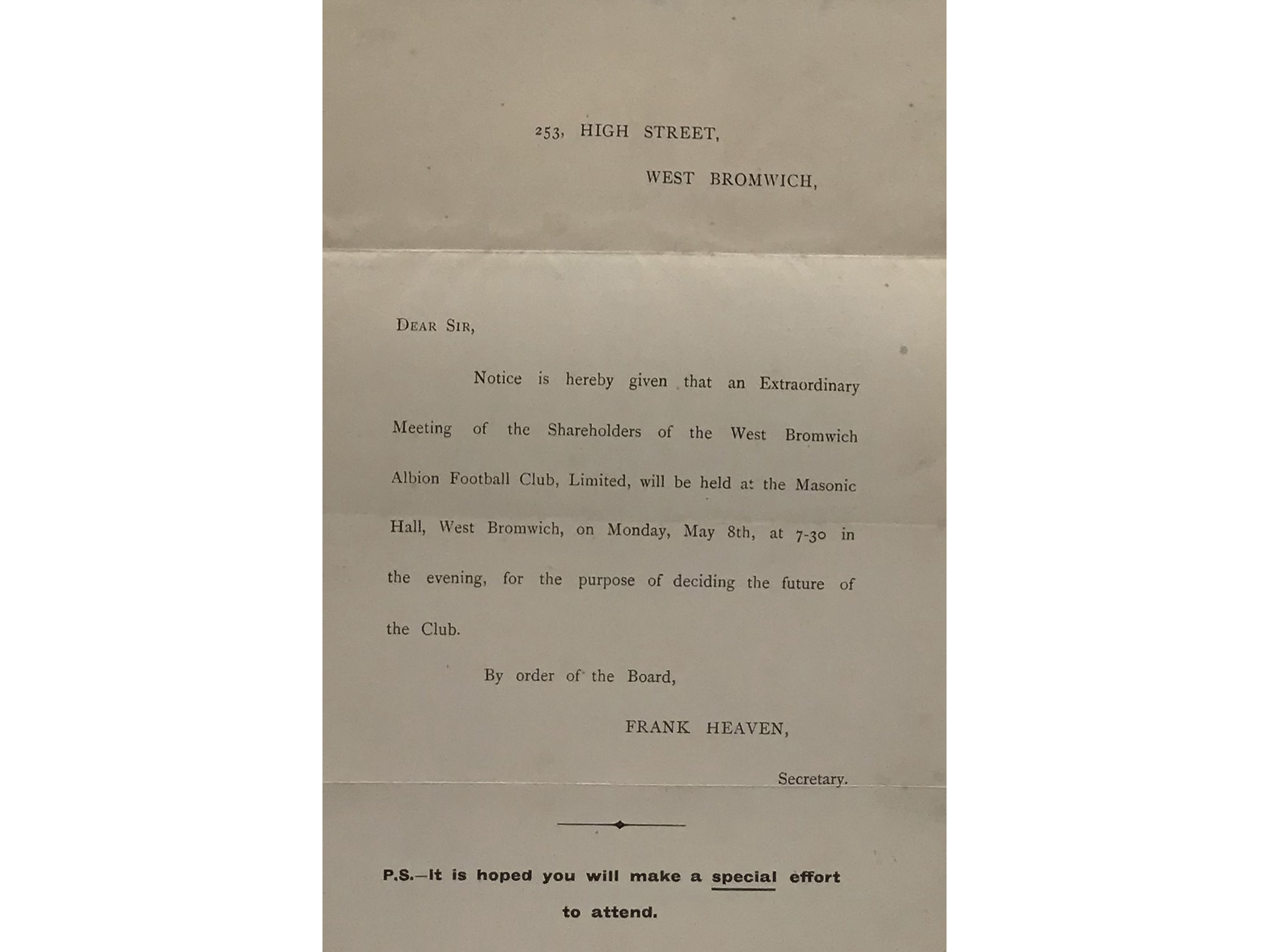

Stuck in Stoney Lane, financial matters deteriorated so badly in the 1898/99 season that a meeting of the club’s shareholders was called for 8 May 1899 to see if it could continue to operate at all, the notice asking them to ‘make a special (underlined!) effort to attend’. At that meeting, those who had earlier offered the £2,500 were called upon to see if their promise remained good. If you’ve ever paid any attention to high finance, you will not be surprised to learn that it did not, and that only around £300 was now on offer to improve Stoney Lane, chicken feed even then. A move was crucial if Albion were to survive. The club had reached a point of no return, from where it simply had to speculate if it was going to accumulate.

But if the move was on, where, exactly, was the club to go?

As the Birmingham Gazette noted, “It was useless looking for a ground in the direction of Hill Top or Great Bridge, as the neighbouring towns of Dudley and Wednesbury, from which in past years a large proportion of the club’s supporters have been drawn, have each now got successful junior football clubs of their own which attract 4,000 or 5,000 spectators to witness their matches. The reduction of the fare of the cable trams to ‘one penny all the way’ and the enormous increase in the populations of Handsworth and Smethwick has made it abundantly clear that any removal of the ground to prove a success must be in the direction of Handsworth”.

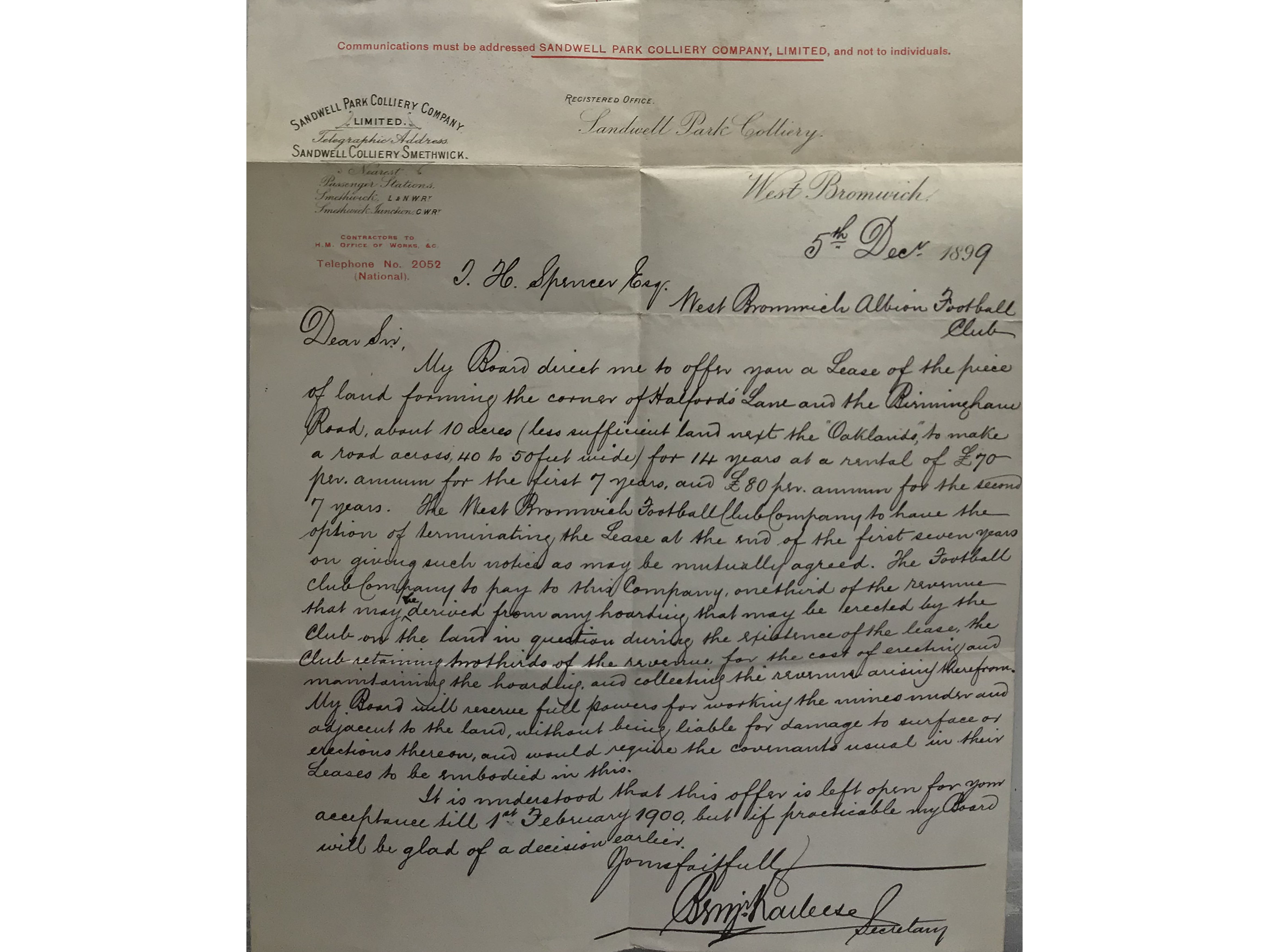

With Albion desperately scouring the locale for an appropriate site for a new ground, the timing could not have been better when, on December 5th 1899, a letter from Benjamin Karliese, the secretary of the Sandwell Park Colliery Company dropped on to the Albion’s doormat.

“My Board direct me to offer you a lease of the piece of land forming the corner of Halfords Lane and the Birmingham Road, about 10 acres (less sufficient land next to the “Oaklands”, to make a road across, 40 to 50 feet wide) for 14 years at a rental of £70 per annum for the first seven years, and £80 per annum for the second seven years. The West Bromwich Albion Football Club Company to have the option of terminating the lease at the end of the first seven years on giving such notice as may be mutually agreed.

“The Football Club Company to pay to the Company one-third of the revenue that may be derived from any hoarding that may be erected by the Club on the land in question during the existence of the lease, the Club retaining two-thirds of the revenue for the cost of erecting and maintaining the hoarding and collecting the revenue arising therefrom.

“My Board will reserve full powers for working the mines under and adjacent to the land, without being liable for damage to surface or erections thereon, and would require the covenants usual in their Leases to be embodied in this. It is understood that this offer is left open for your acceptance till 1st February, 1900, but if practicable my Board would be glad of a decision earlier”.

To translate, if your centre-forward suddenly dropped 250 feet through a hole in the six-yard box and down to the mine workings below, it would be, in a very real and legally binding sense, the club’s problem.

The Birmingham Gazette noted that this approach was a particularly pleasing development and that the plot in question fitted the bill perfectly, for the proposed site had good access, wide roads coming up to the ground from West Bromwich, Smethwick and Birmingham, although the later arrival of the motor car meant that easy post-match departures would eventually become a thing of the dim and distant past. But back then, with the main tram routes into Birmingham running right past the site, the perfect location had dropped into the laps of the Albion directors.

“A suitable piece of land was noted at the corner of Halford’s Lane on the main road, about halfway between the New Inns at Handsworth and the Dartmouth Hotel at West Bromwich. Its situation is believed to be even better than the ground near the Beeches Road which was proposed [in 1898], being easier of access from large centres of population.

“On the Handsworth side of it, a new street will be cut leading into Island Road, so that entrances to the ground can be made from three separate and wide roads, and with ten acres of land there will be abundance of room for all requirements. It will be easy of access from all parts, and it should be the commencement of a new lease of life for the club. The ground will have to be drained and relaid and suitable stands for the accommodation of the people provided. We are not in a position to state definitely as yet how the money will be raised, but we understand the directors can see a way of doing this without touching the funds of the club”.

Essentially, the plot was an area of marshland in a rural location. There was a brook running diagonally through what was effectively a meadow, the brook forming a border between Smethwick, Handsworth and West Bromwich. The Woodman Inn (of blessed memory) was on the Handsworth side, along with a blacksmith’s forge and a few houses. At the Smethwick end was a large house, Oaklands, and a garden nursery. A large private house was to one side of the land. It later became The Hawthorns Hotel and housed many Albion players – the great Ray Barlow got word of his first England call up there – and is now Greggs. From the sublime to the vegan sausage roll.

The amount of money available for undertaking all this work was a mere £1,800, but this did not deter the directors of the club who realised this was the route to the club’s ultimate salvation, the chairmanship of the newly installed Major H. Wilson Keys particularly crucial in driving the idea through. But we like a bit of brinkmanship at West Bromwich Albion, and so it was not until January 30th 1900 that the club accepted the proposal, signed the papers and the move became a reality.

But what to name the new place? Frank Heaven, Albion’s secretary-manager of the time, had done a little research on the site and had been told that in previous years, it had been part of an estate covered in trees, bushes and wildlife. Given the relationship between the throstle and the most prevalent of those trees, what better name than that of the original estate?

Welcome to The Hawthorns.

Albion will honour 125 years at The Hawthorns with a specially-designed home kit for the 2025/26 season.

The contemporary blue-and-white-striped shirt – designed by the club and Technical Partner Macron – draws inspiration from the jersey worn when the Baggies first walked out at The Hawthorns in 1900.

Tony ‘Bomber’ Brown – the player who holds the record for most appearances at The Hawthorns – stars in the club’s kit launch video and the quote affixed to his statue.

The inside neckline includes an image of The Hawthorns, while anniversary logos adorn the front and back of the shirt – which will be worn with navy socks and white shorts by the men’s first team, while the women’s first team will continue to wear navy shorts and socks.

An internal QR code – which can be scanned with a smartphone – will bring the kit to life throughout the anniversary campaign, with newly-appointed Club Historian Dave Bowler curating 125 unique pieces of Hawthorns content.

Every supporter who buys the new home shirt before August 1 will receive an A5 postcard featuring the poem narrated by Tony Brown in the kit launch video and a ‘Bomber’ moustache to create their very own memories. Fans can post their photos on social media using the hashtag #BomberMoustache – and the club will share its favourites.